Javanese Batik

Hand-drawn batik (batik tulis) can only continue to flourish as an Indonesian art form through its production, distribution and wear.

Indonesian Batik Textiles: The Diversity of Tradition

In Indonesia, batik textiles, which have been produced since the early seventeenth century, remain integral to everyday life, and often play a role in key events such as births, weddings, and funerals.* UNESCO added Indonesian batik to its Representative List of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2009, noting that the making of the textiles and their use are central to Indonesian culture.

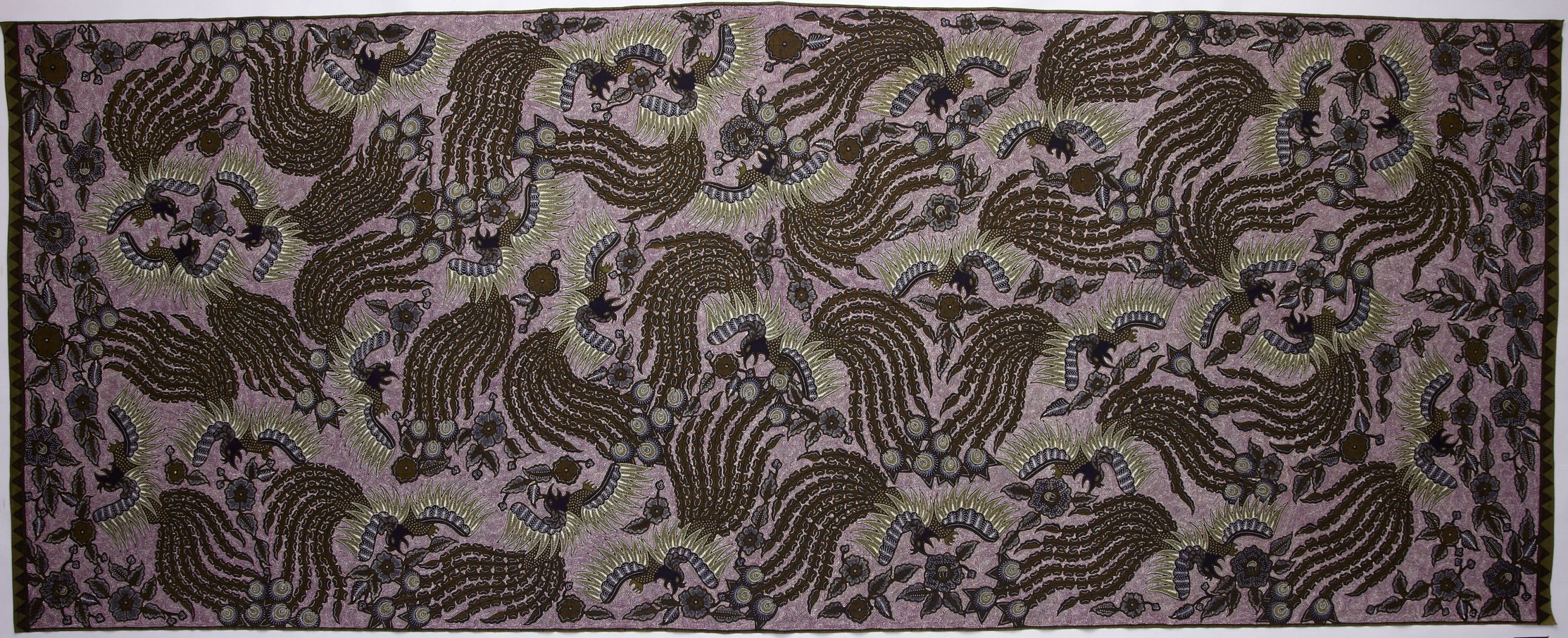

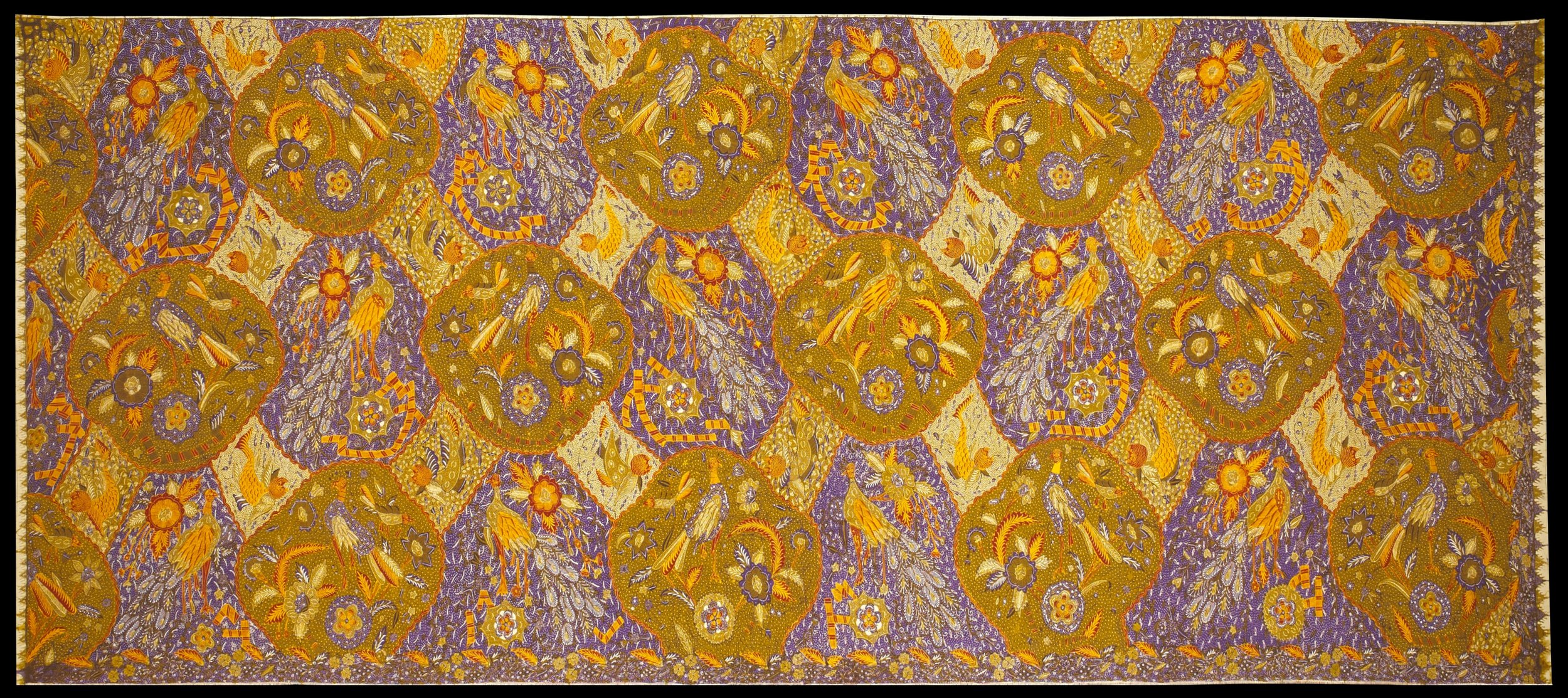

Female Javanese Birth Calendar. Long Cloth, produced by Kushardjanti, Yogyakarta, about 1978. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist, 101 x 260 cm.

Batik is a textile design technique based on resist-dyeing. A plain cotton or silk cloth serves as the ground.** To begin, an artist makes a drawing on paper, and this drawing is then stenciled on the cloth, providing a guide for the application of hot liquid wax. The process for applying the wax distinguishes batik tulis or hand-drawn batik from batik cap or printed batik. As the names indicate, to create batik tulis, an artist applies (hand-draws) the wax with a canting (a pen with a reservoir for the wax) following and interpreting the stenciled design. To create batik cap, a block with a pattern is dipped in wax and stamped on the cloth. The cap speeds up the process, however, it cannot be used for all designs. In both processes, after the wax has cooled, the cloth is submerged in a dye bath and the areas without wax take on color, while the wax-covered areas “resist” the dye. Depending on the number of colors in the design, the wax application and dyeing process may need to be repeated multiple times.

Batik artists drawing designs in wax with cantings.

Indonesian batiks capture and convey the diverse forces that have shaped their facture across centuries. Scholars, such as Ruth Barnes, Peter Carey, and Rens Heringa, emphasize the importance of Java as a center of multicultural batik production, although the precise origin of the technique remains a matter of ongoing debate. Regardless, it is clear that Indonesia’s central location in the Indian Ocean world, facilitating the movement of people and material goods to and from China, India, and Japan, and later Europe, paired with ready access to indigenous materials required in the production process, has fostered a vibrant and ever-changing artistic practice. Batik artists have experimented with color, layout, and pattern as they adapt, incorporate, and interpret elements drawn from embroidered, painted, and woven trade textiles (as well as other art objects) into their work. Moreover, immigrants to Indonesia have brought their aesthetic knowledge with them and embraced batik as a mode of artistic expression as well as a viable commercial enterprise.

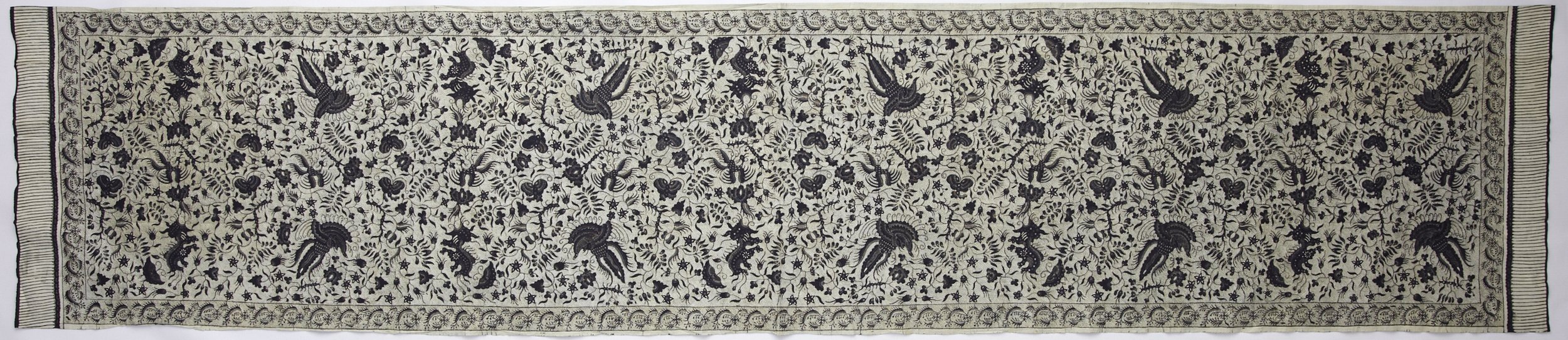

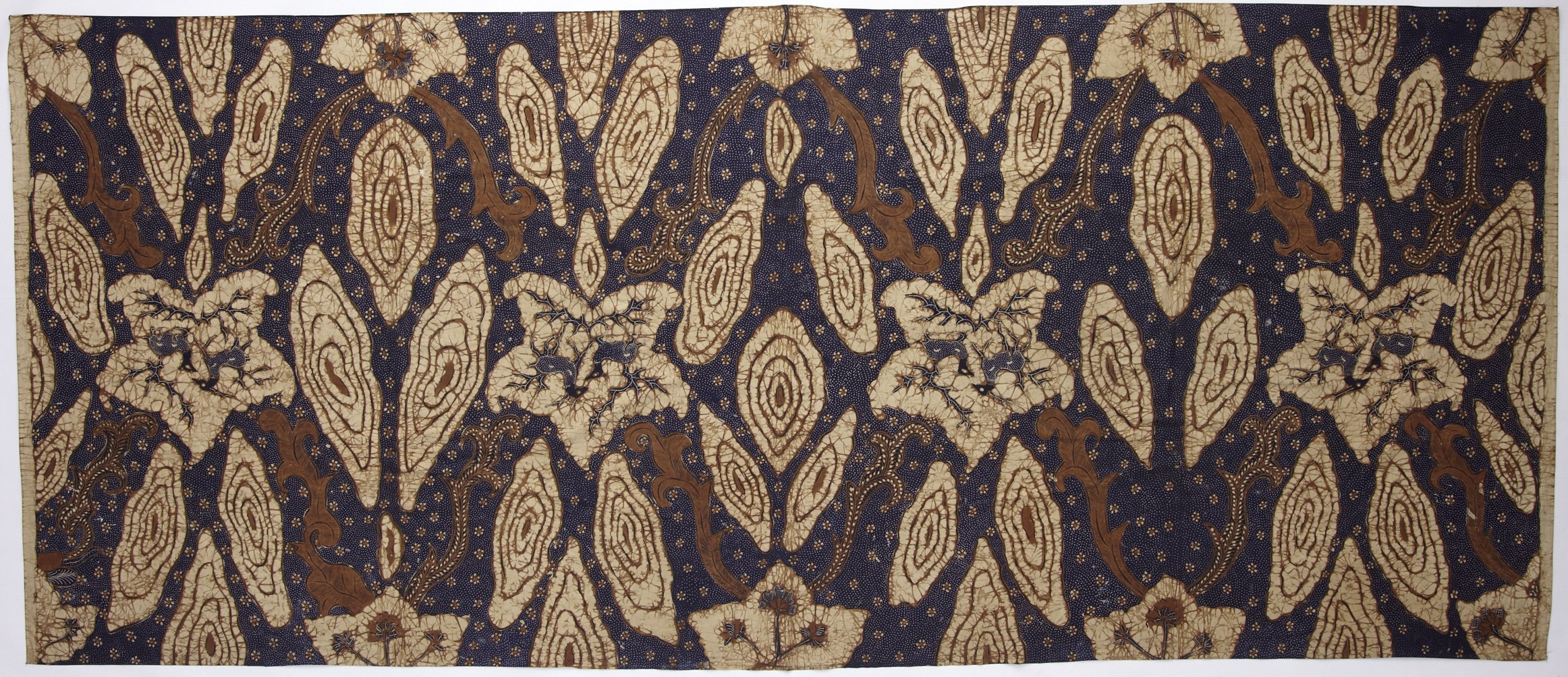

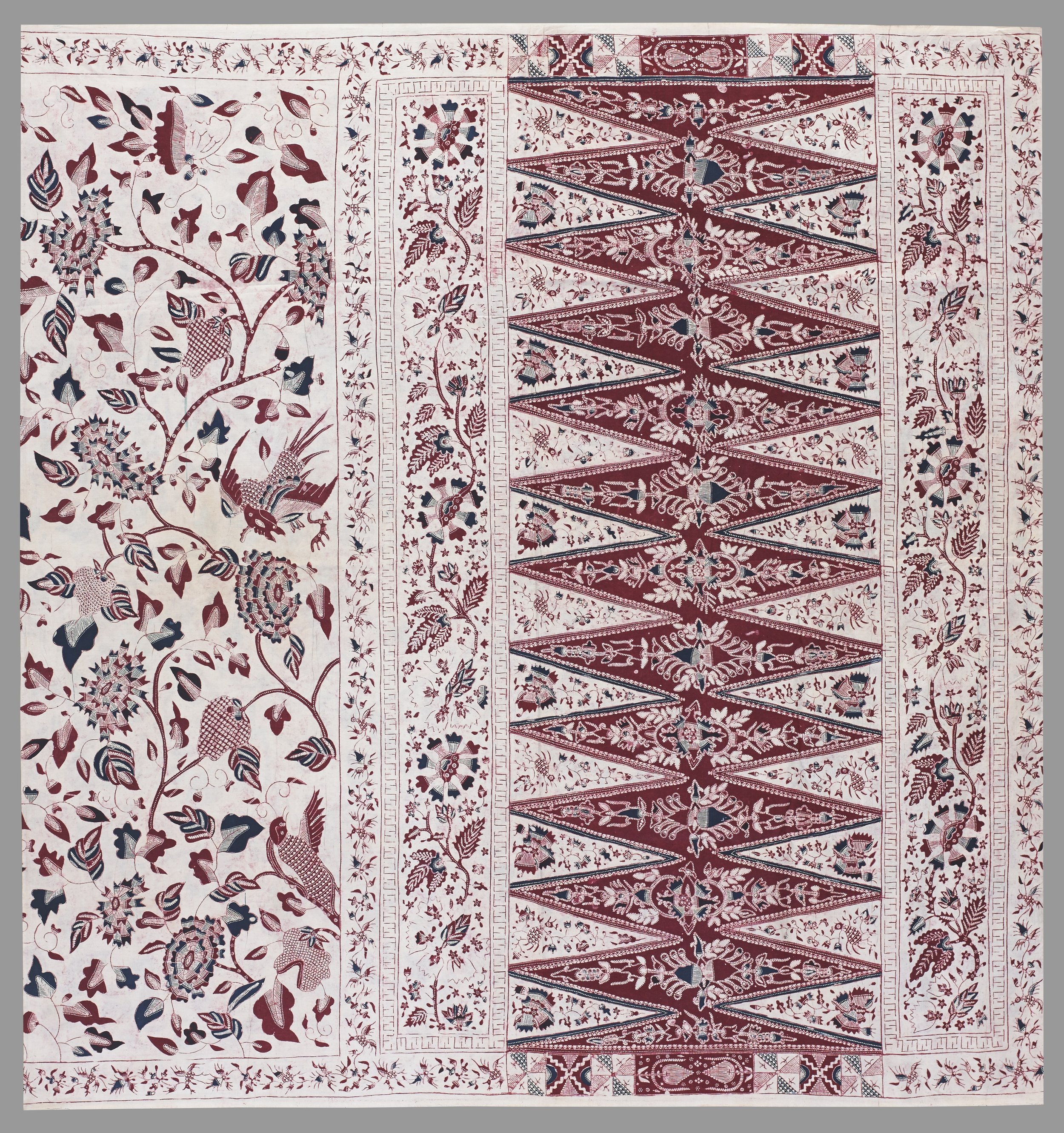

Deer in the Jungle. Long Cloth, produced in Cirebon, about 1920. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand drawn wax resist, 103 x 250 cm.

Batik designers’ adaptation of elements from Chinese textiles surface in a number of works in Dr. Indriati’s collection. A blue and white Long Cloth (Deer in the Jungle) from about 1920 features delicately leaping deer, detailed butterflies and stylized clouds, the two latter motifs ubiquitous in Chinese textiles. Moreover, the color palette suggests an appreciation of ceramics, particularly blue and white porcelain. The butterfly motif also appears on an earlier batik from 1900 (Serendipity) that has a pronounced geometric design, which resembles the fretwork patterns often featured in Chinese art and design (for example, this Sutra Cover in the Metropolitan Museum of Art collection). As this batik dates to the turn of the century, it is possible that the designer drew visual inspiration from European Aesthetic Movement and/or Art Nouveau furnishings (or furnishings from earlier periods), which amalgamated elements of Chinese art and design. These batiks thus illuminate the complexities of coloniality and culture in the Indian Ocean world across centuries.

Detail, Deer in the Jungle.

Detail, Serendipity. Long Cloth, produced in Garut, about 1900. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 106 x 249 cm.

Detail, Sutra Cover with Multicolored Clouds on an Overall Fretwork, produced in China during the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), 16th century. Woven, 13 5/16 x 4 13/16 x 1/4 inches.

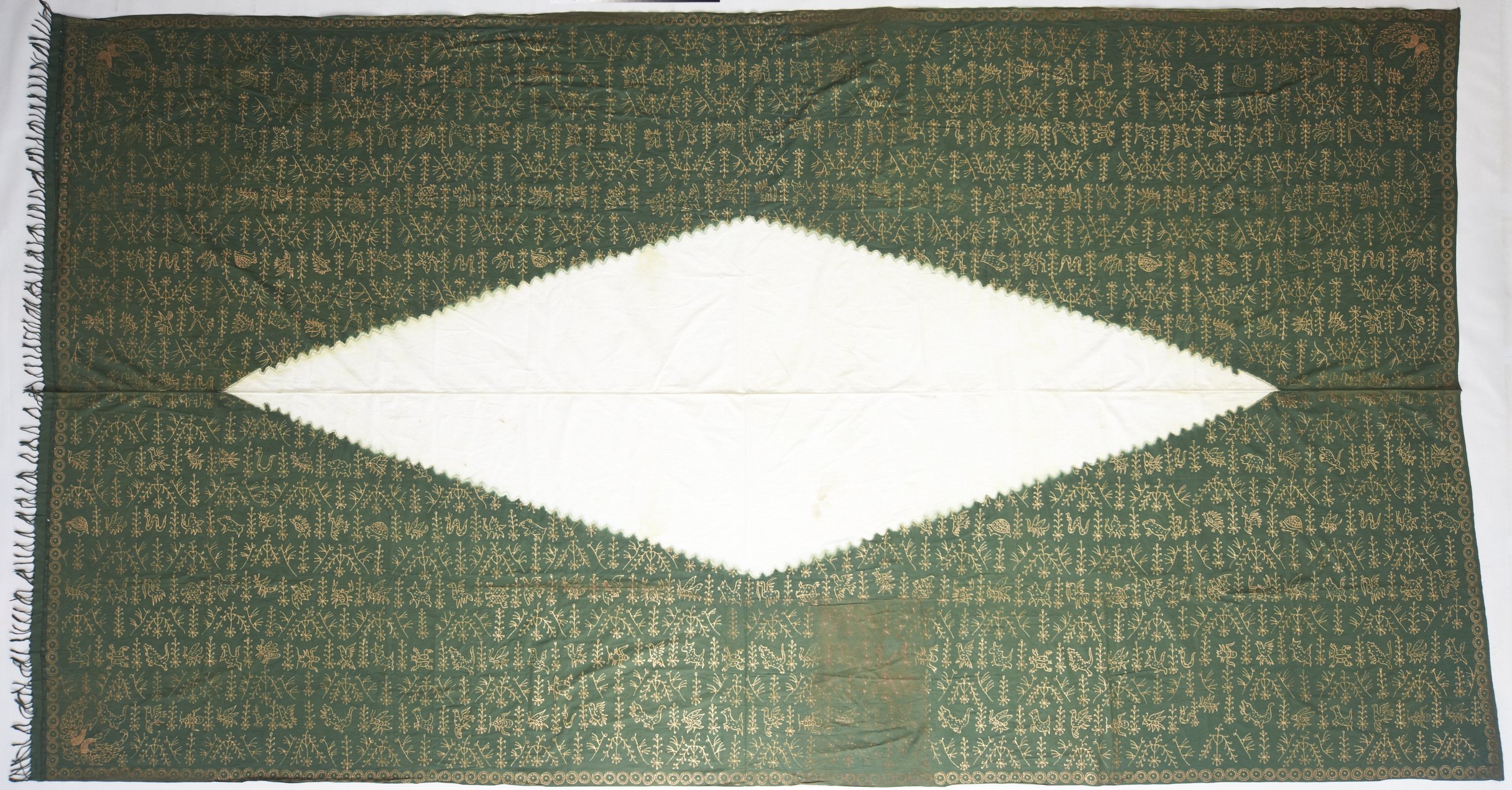

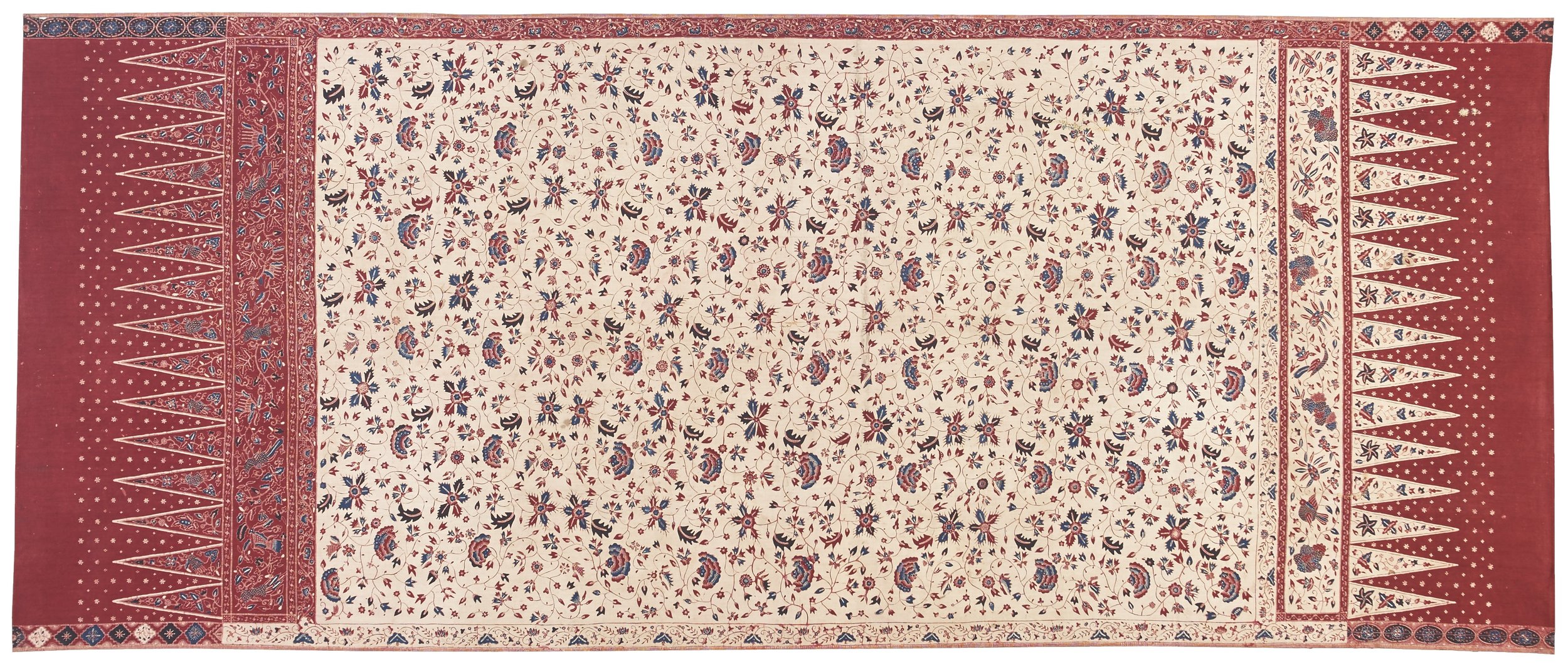

A batik produced in Cirebon, on the northwestern edge of Java, around 1900 (Calligraphic Composition), demonstrates the impact of Islamic art, beliefs, and culture on batik artists and consumers (Islam currently is the predominant faith of people living in Indonesia, and has been since the seventeenth century). The densely patterned scarf features three large eight-pointed stars, or pairs of overlapping squares (rub-el-hizb), and a profusion of looping and scrolling elements that suggest Arabic calligraphic inscriptions as well as apotropaic symbols. The left and right borders of the scarf include a repeating motif that suggests an enclosed bit of script. The framing of text within a larger design likely borrows from established Islamic aesthetic convention (for example, this woven silk and silver textile from Iran (3.280) in the collection of the Textile Museum in Washington, DC).

Calligraphic Composition. Head Scarf, produced in Cirebon, about 1900. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 84 x 215 cm.

Detail, Calligraphic Composition.

The Islamicate designs of this scarf resonate strongly with a batik head cloth from Cirebon made during the same period (Basurek Headdress). The head cloth has a mirror repeat with a small-scale geometric ground pattern that references the overall mirrored design. This head cloth also bears a striking similarity to a batik (1987.26.1) in the collection of the Textile Museum in Washington, DC. The border of the Textile Museum’s batik features multiple registers that are echoed in the Basurek Headdress. The breadth and quality of Dr. Indriati’s collection emphasizes the significance of batik textiles across Java and the contemporary works, such as Happy Garden, highlight that the exchange of design knowledge within the Indian Ocean world continues to foster the flourishing of batik as a diverse artistic practice.

Basurek Headdress. Head Cloth, produced in Cirebon, about 1900. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 90 x 92 cm.

Detail, Happy Garden. Long Cloth, signed by Sapuan, Pekalongan, about 2010. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 104 x 266 cm.

Notes

*In Fabric of Enchantment: Batik from the North Coast of Java, From the Inger McCabe Elliott Collection at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (1996), Rens Heringa asserts that batik tulis “may not have developed until the early seventeenth century” but goes on to clarify “The decoration of textiles with a resist technique has probably existed in the archipelago since prehistoric times, although no examples predating the nineteenth century survive” (31). Further research may bear out a more specific date for the development of batik tulis, and indeed Ruth Barnes research on carbon dating textiles (“Early Indonesian Textiles: Scientific Dating in a Wider Context”) in the 2010 catalogue Five Centuries of Indonesian Textiles: The Mary Hunt Kahlenberg Collection presents exciting possibilities for potentially identifying earlier examples.

**In 2009 Yosephine Komara of BINhouse, along with her husband Roni Siswandi, pioneered batik on cashmere.

Essay by Dr. Erica Warren; you can find more information about Dr. Warren on her website.

References

Judi K. Achjadi and Asmoro Damais. 2006. Butterflies and Phoenixes: Chinese Inspiration in Indonesian Textile Arts. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Editions.

Ruth Barnes and Mary Hunt Kahlenberg, eds. 2010. Five Centuries of Indonesian Textiles, New York: Delmonico Books.

Ruth Barnes, 1996. “Early Indonesian Textiles: Scientific Dating in a Wider Context” in Fabric of Enchantment: Batik from the North Coast of Java: From the Inger McCabe Elliott Collection at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Los Angeles County Museum of Art and Weatherhill, Inc.

Peter Carey, 1996. “The World of the Pasisir” in Fabric of Enchantment: Batik from the North Coast of Java: From the Inger McCabe Elliott Collection at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Los Angeles County Museum of Art and Weatherhill, Inc.

Rens Heringa, 1996. “The Historical Background of Batik on Java” in Fabric of Enchantment: Batik from the North Coast of Java: From the Inger McCabe Elliott Collection at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Los Angeles County Museum of Art and Weatherhill, Inc.

Dr. Indriati’s Batik Collection

Misty Morning on the Beach. Long cloth, produced by BIN House, Jakarta, about 2011. Hand woven silk, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 107 x 235 cm.

Lemon Yellow Mixed Patterns. Stole, produced by BIN House, Jakarta, about 2011. Hand woven silk, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 106 x 199 cm.

Bondet. Long cloth, produced by BIN House, Jakarta, about 2011. Hand woven silk, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 110 x 214 cm.

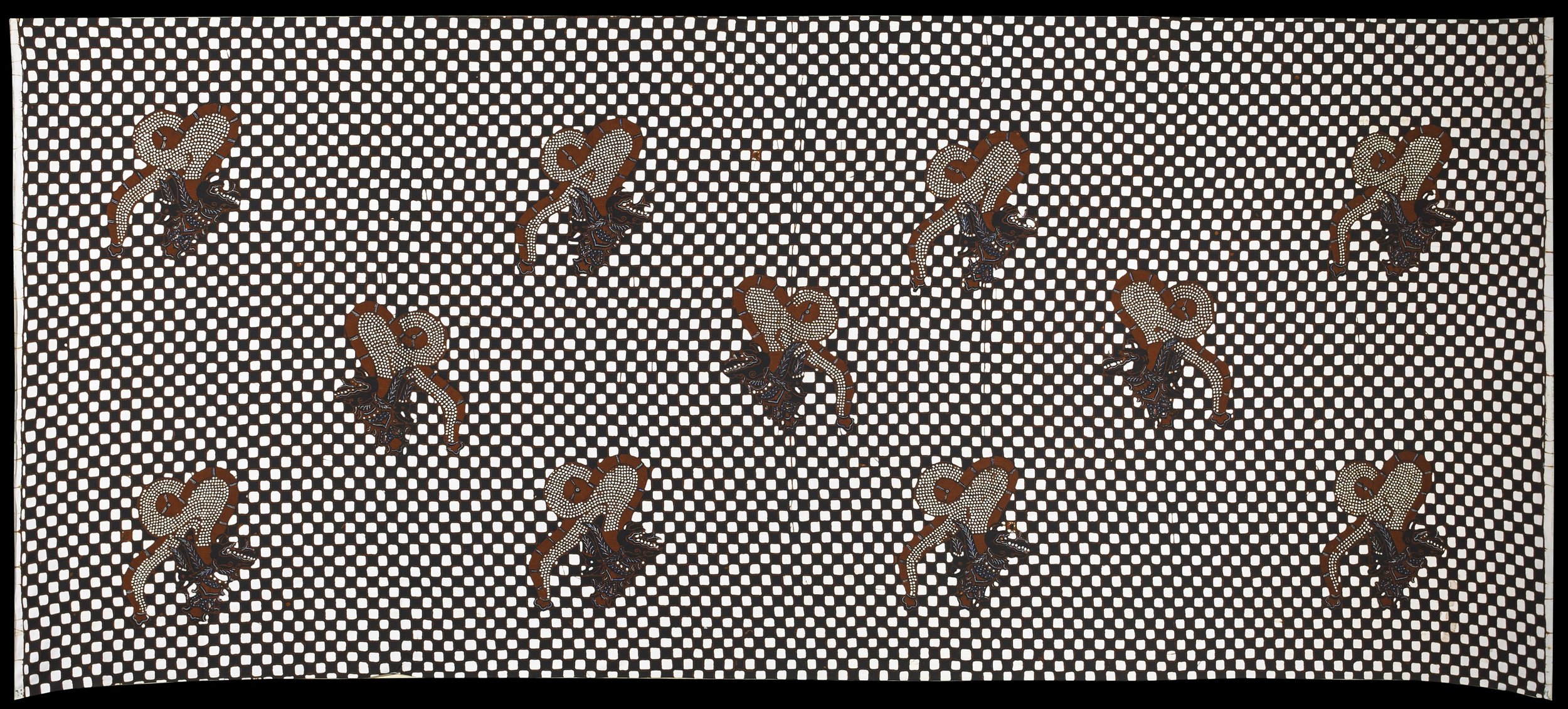

Cock Fight (Sacrifice for the Earth). Long Cloth, produced by K.R.T. Hardjonagoro Go Tik Swan, Surakarta, about 2011. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 103 x 263 cm.

Javanese Dragon King. Wall Hanging, produced by Iwan Tirta, Jakarta, about 2009. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, had drawn wax resist dye, 114 x 213 cm.

Lucky Frogs Composition. Long Cloth, produced by Dhaimeler, Jakarta, about 2011. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 116 x 228 cm.

Kilin (Mythical Chinese Animal). Shoulder Cloth, produced in Indramayu, about 1900. Silk, natural dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 53 x 250 cm.

Calligraphic Composition. Head Scarf, produced in Cirebon, about 1900. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 84 x 215 cm.

Battlefield. Long Cloth, produced in Cirebon, about 1900. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 105 x 247 cm.

Basurek Headdress. Head Cloth, produced in Cirebon, about 1900. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 90 x 92 cm.

Rafiah. Head Cloth, produced in Cirebon, about 1900. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 102 x 103 cm.

Rafflesia Patchwork. Shoulder Cloth, produced in Cirebon, about 1900. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 103 x 244 cm.

Deer in the Jungle. Long Cloth, produced in Cirebon, about 1920. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 103 x 250 cm.

Tambal Pamiluto (Love and Attraction). Long Cloth, produced in Surakarta, about 1950. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 104 x 241 cm.

Dodot (Wedding Attire). Dodot/Kampuh, produced by K.R.T. Hardjonagoro Go Tik Swan, Surakarta, about 1970. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 204 x 386 cm.

Raditya Kusumo on Nitik. Long Cloth, produced by K.R.T. Hardjonagoro Go Tik Swan, Surakarta, about 2011. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 104 x 262 cm.

Twenty Flying Birds. Long Cloth, produced in Cirebon, about 1972. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 105 x 265 cm.

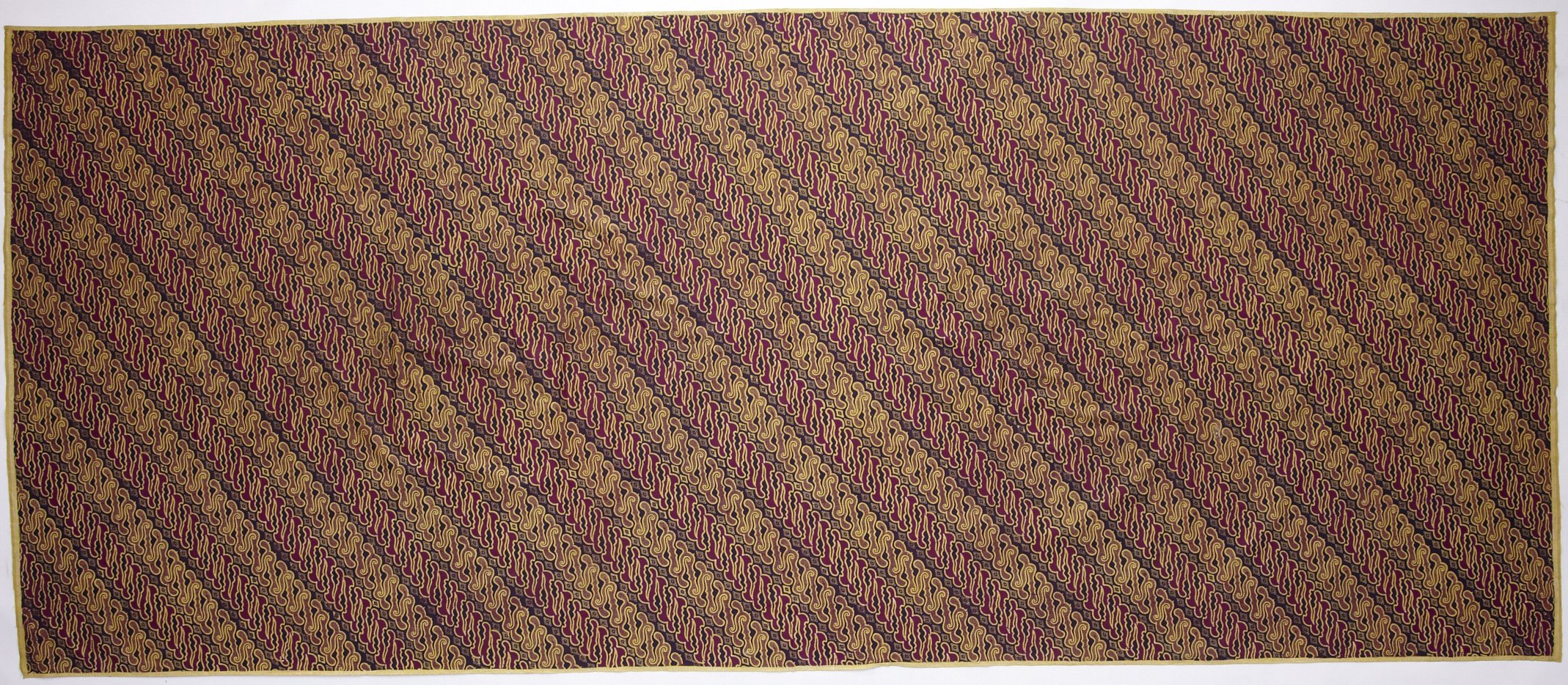

Parang Composition. Long Cloth, Produced in Garut, about 1950. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 106 x 254 cm.

Big Birds in the Garden. Long Cloth, produced in Banyumas, about 1930. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 104 x 268 cm.

Celana Pangsi. Long Pants Material, produced in Pekalongan, about 1910. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 105 x 150 cm.

Proud Peacocks. Long Cloth, produced in Sidoarjo, about 1950. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 104 x 217 cm.

Peacock and Butterfly. Long Cloth, produced in Pekalongan, about 1942. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 110 x 241 cm.

Happy Garden. Long Cloth, signed by Sapuan, Pekalongan, about 2010. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 104 x 266 cm.

Rainbow. Scarf, produced by APIP Kerajinan Batik, Yogyakarta, about 2012. Silk, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 78 x 213 cm.

Flash Gordon. Long Cloth, produced in Surakarta, about 1950. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 105 x 247 cm.

Seca (Aging Tree Slice). Long Cloth, produced in Surakarta, about 1950. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 102 x 244 cm.

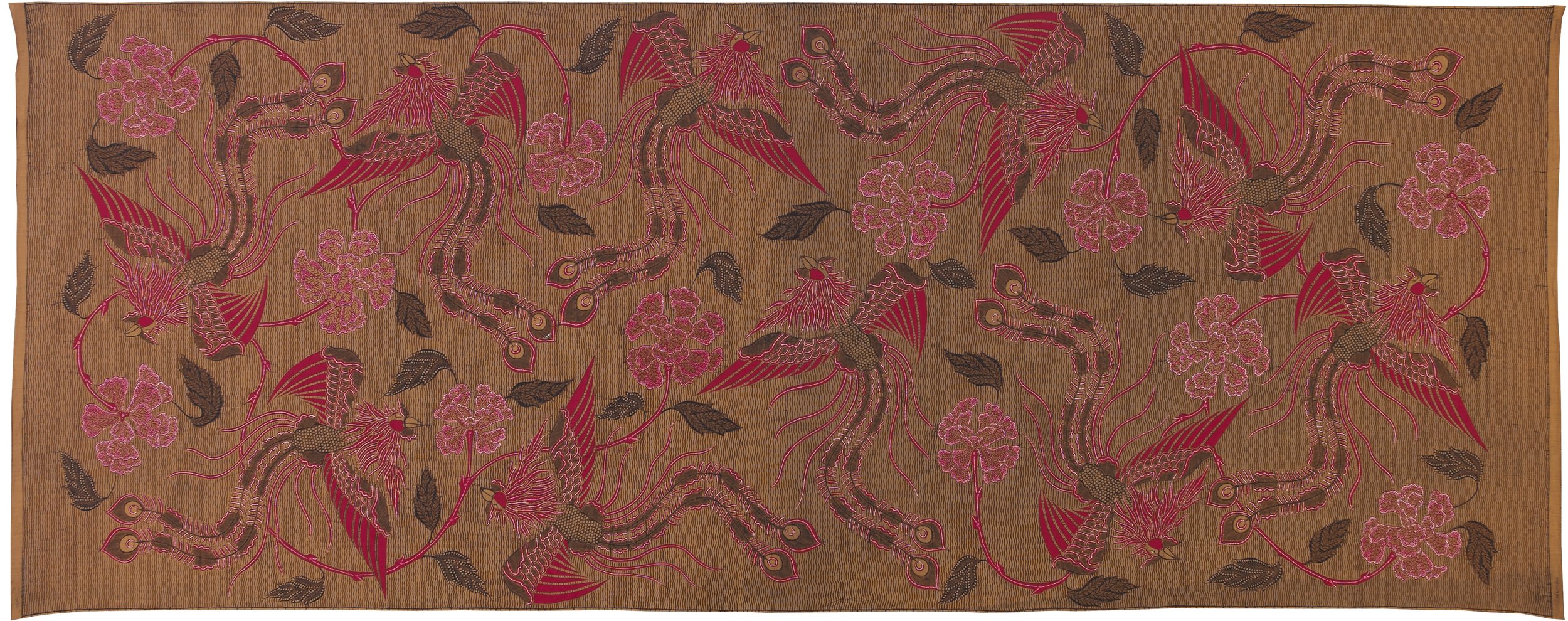

Flying Phoenix. Long Cloth, produced by K.R.T. Hardjonagoro Go Tik Swan, Surakarta, about 2011. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 104 x 263 cm.

Tirtateja (Water Reflection). Long Cloth, produced by Hani Winotosastro, Yogyakarta, about 1980. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 104 x 254 cm.

Fuschia Heaven. Long Cloth, signed by Sapuan, Pekalongan, about 2010. Machine spun cotton, sythetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 104 x 268 cm.

Destiny. Long Cloth, signed by Sapuan, Pekalongan, about 2010. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 104 x 265 cm.

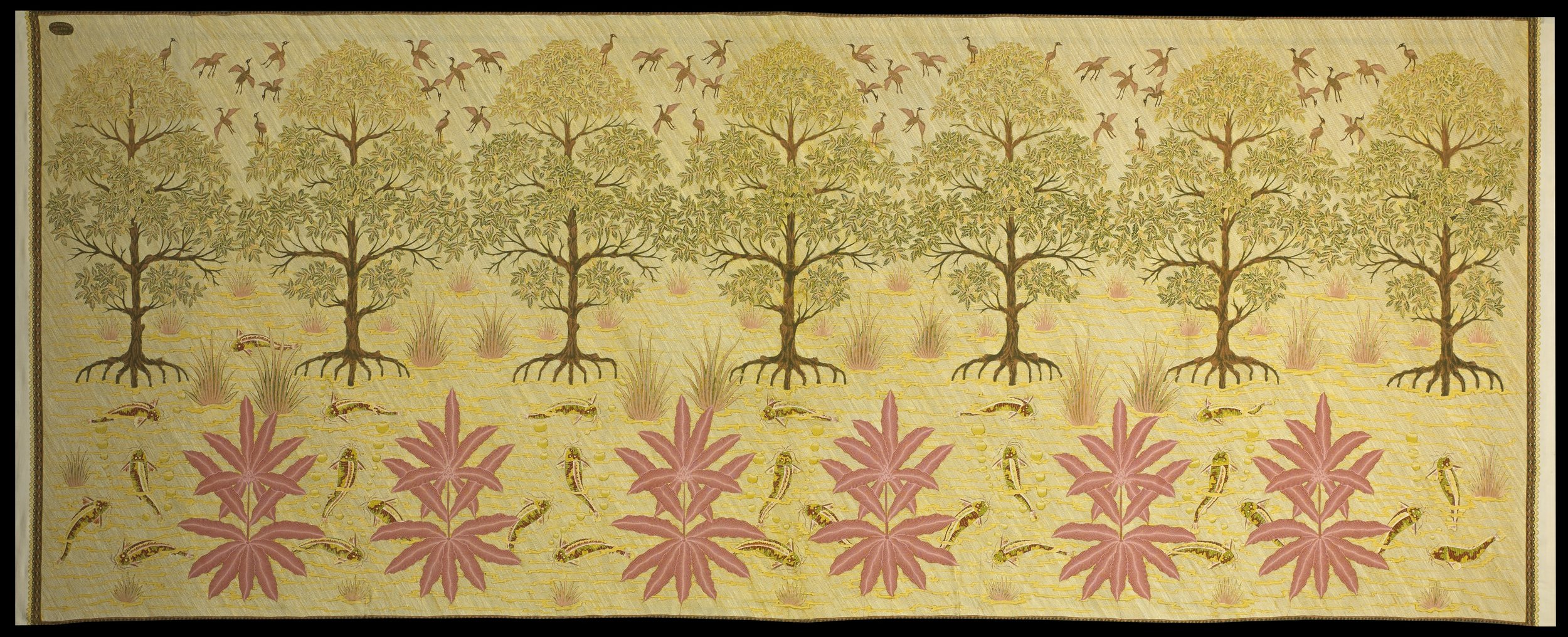

Tree of Life. Long Cloth, produced in Kudus, about 1900. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 104 x 249 cm.

Magnolia Champaca. Head Scarf, produced for Lasem for Jambi, Sumatra, about 1900. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 92 x 225 cm.

Geometric Composition. Long Cloth, produced in Lasem for Sumatra, about 1930. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand drawn and wood-stamp wax resist dye, 103 x 228 cm.

Bangbangan. Head scarf, produced in Lasem, about 1900. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 89 x 208 cm.

Kupu-kupu. Long Cloth, signed by The Tjing Sing, Yogyakarta, about 1935. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 105 x 264 cm.

Female Javanese Birth Calendar. Long Cloth, produced by Kushardjanti, Yogyakarta, about 1978. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 101 x 260 cm.

Bangbiron. Long Cloth, produced in Lasem, about 1930. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 107 x 269 cm.

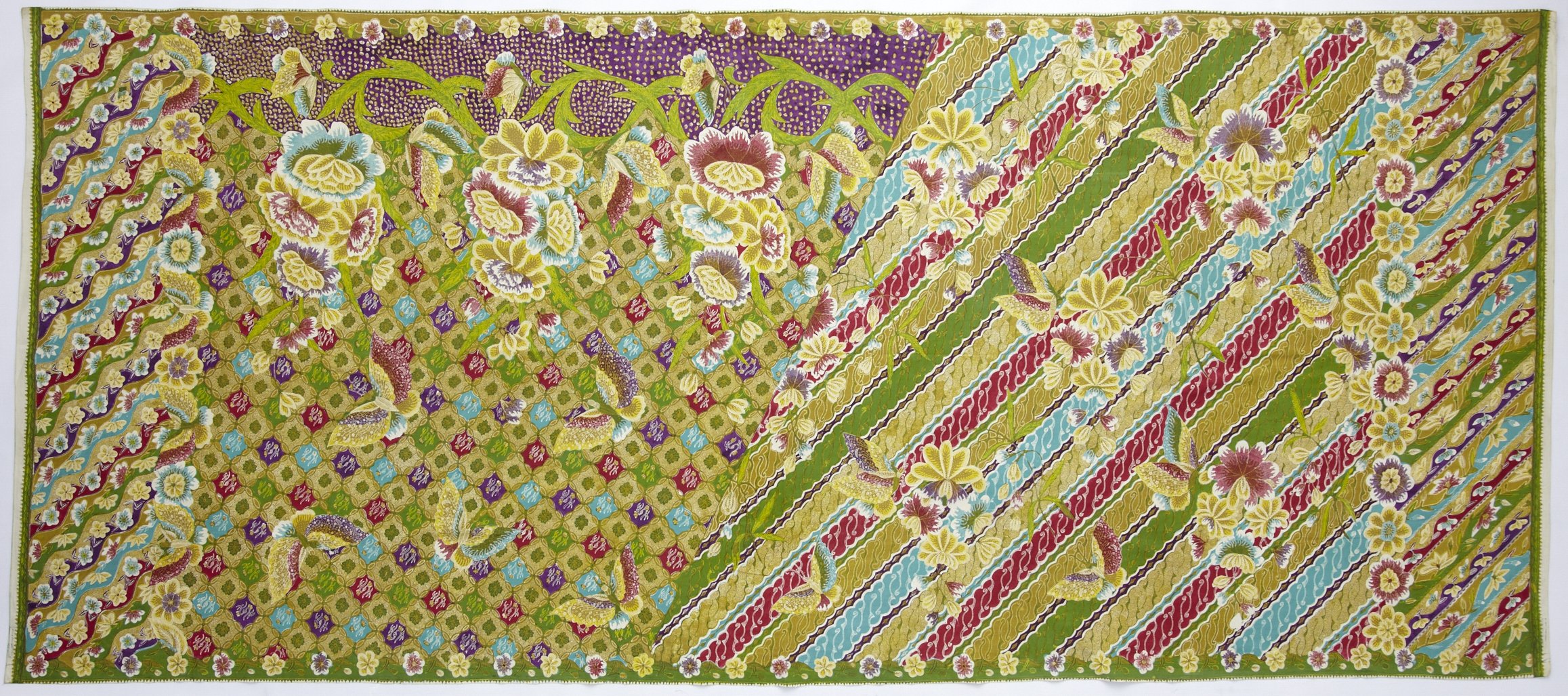

Java Hokokai Composition. Long Cloth, produced in Pekalongan, between 1940-1950. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 103 x 250 cm.

Interlocking Luck. Shoulder Cloth, produced in Rembang or Juana, about 1900. Silk, natural dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 56 x 236 cm.

The Guardian of the Night. Long Cloth, produced by K.R.T. Hardjonagoro Go Tik Swan, Surakarta, n.d. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 103 x 263 cm.

The Tjing Sing Signature. Long Cloth, signed by The Tjing Sing, Yogyakarta, about 1935. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 105 x 267 cm.

Trenggiling Mentik (Respect for Others). Long Cloth, produced in Surakarta, about 1950. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 104 x 253 cm.

Go Hunting. Long Cloth, produced in Surakarta or Yogyakarta, about 1950. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 104 x 246 cm.

Opium Flower. Long Cloth, produced by K.R.T. Hardjonagoro Go Tik Swan, Surakarta, about 2010. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 105 x 261 cm.

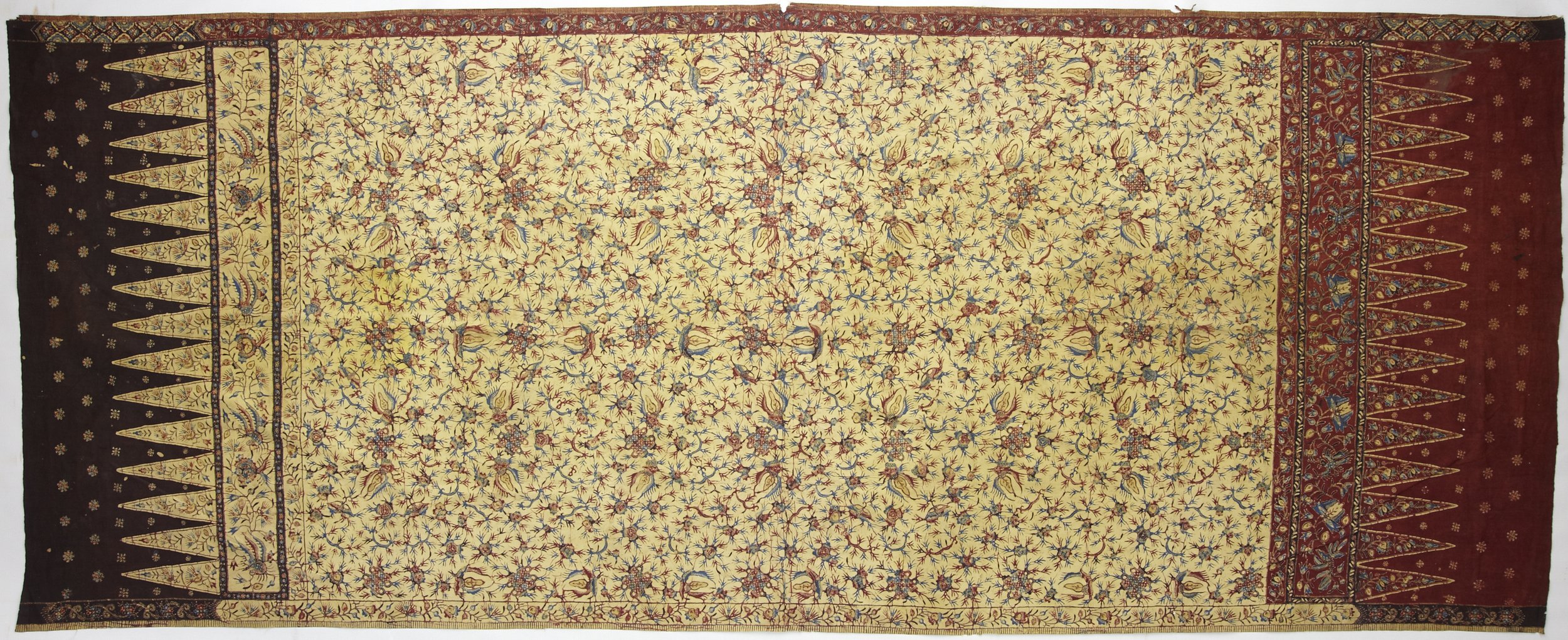

Tiga Negeri. Tubular Cloth, produced by Tiga Negeri, Solo-Lasem-Kudus, about 1900. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 93 x 210 cm.

Tiga Negeri. Tubular Cloth, produced by Tiga Negeri, Solo-Lasem-Kudus, about 1900. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 105 x 200 cm.

Purple Boat Parade. Tubular Cloth, produced by Setiawati, Jakarta, about 1960. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 105 x 188 cm.

Reaching the Moon. Long Cloth, produced by Tatik Sri Harta, Sragen, Surakarta, about 2010. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 105 x 242 cm.

Peacocks in Pink Composition. Tubular Cloth, produced by Setiawati, Jakarta, about 1960. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 104 x 188 cm.

Garden of Java. Long Cloth, produced in Pacitan, about 1950. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 105 x 248 cm.

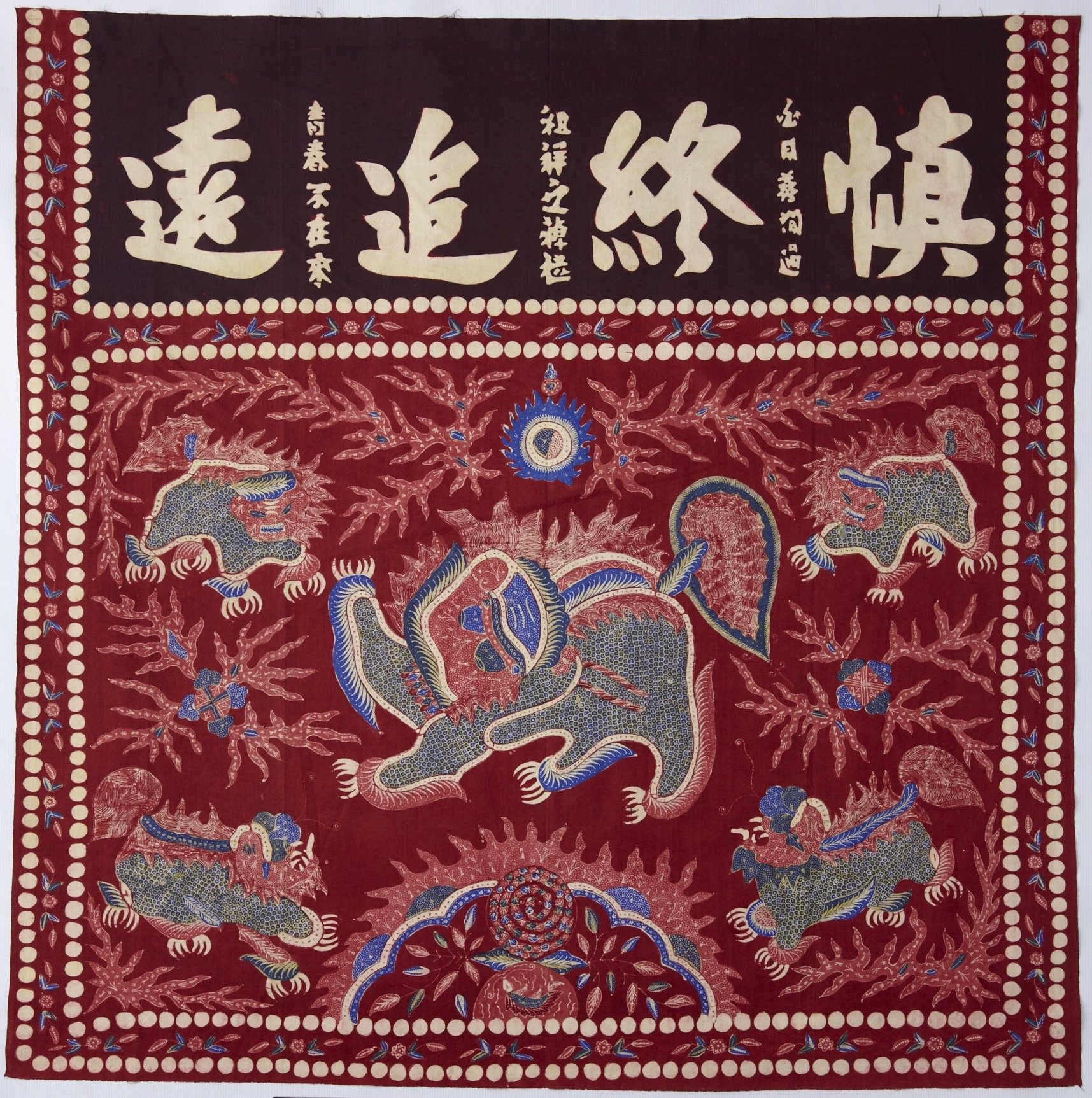

Kilin. Thok Wie Altar Cloth, produced in Pekalongan, about 1900. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 103 x 104 cm.

Fan Composition. Long Cloth, produced in Surakarta, about 1950. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 104 x 248 cm.

Ayam Alas. Tubular Cloth, signed by Lo Siok Tjwan, Batang, about 1950. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 105 x 202 cm.

Taman Teratai. Tubular Cloth, produced by Lie Boen In, Kudus, about 1930. Machine spun cotton, natural (and synthetic?) dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 99 x 214 cm.

Parang Curigo. Long Cloth, attributed to Kho Sing Kie Atelier, Banyumas, 1933-1950. Machine spun cotton, natural or synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 107 x 232 cm.

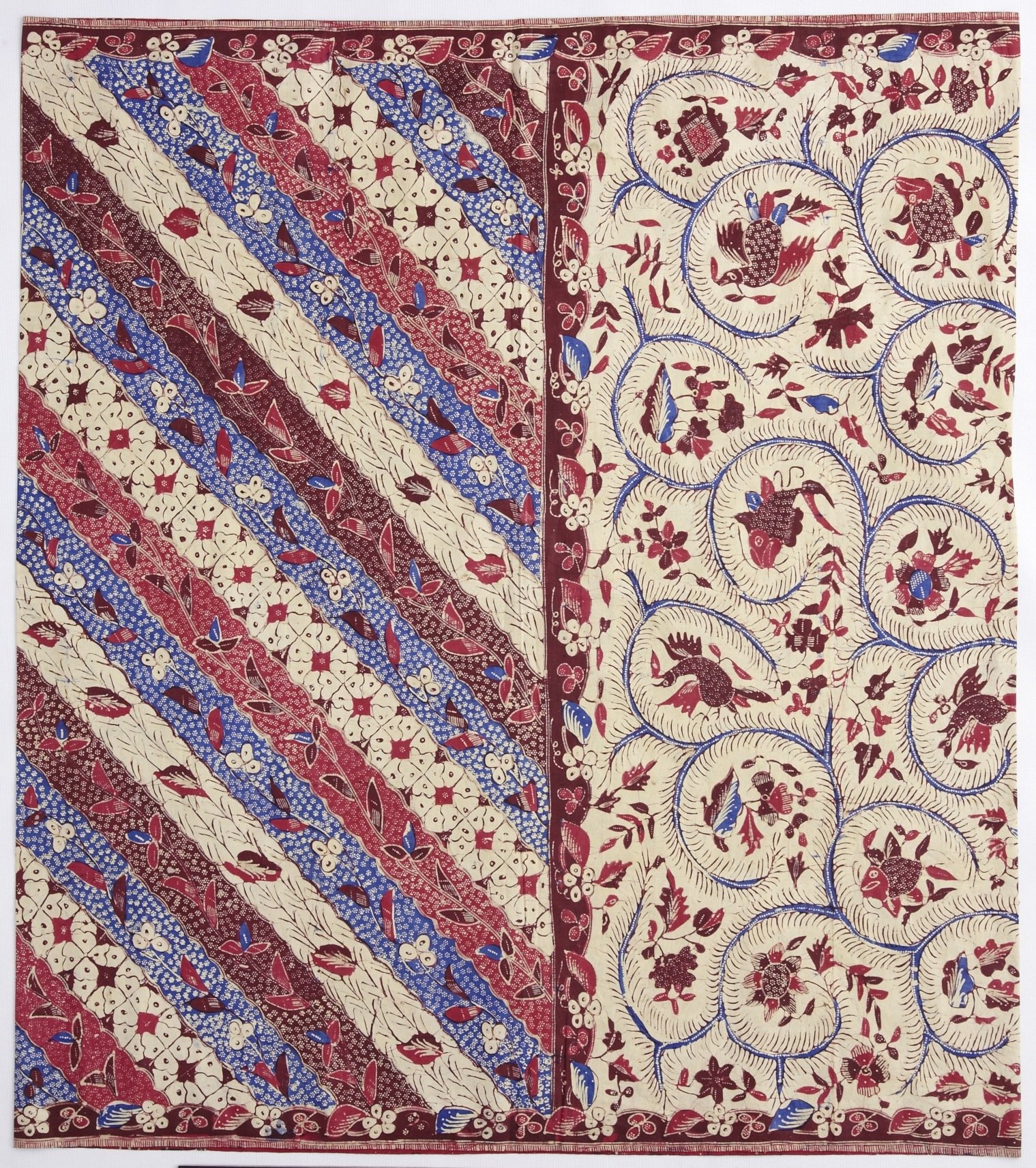

Diagonal Composition. Long Cloth, produced in Kudus, about 1900-1920. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 103 x 253 cm.

Diagonal Composition. Long Cloth, produced in Lasem, about 1900. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 108 x 202 cm.

Serene Green and Aristocratic Motif in Brown. Long Cloth, signed by Oey Soe Tjoen, Pekalongan, 1932-1950. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 105 x 258 cm.

Half and Half Composition. Head Cloth, produced in Lasem, about 1900. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 102 x 103 cm.

Serendipity. Long Cloth, produced in Garut, about 1900. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 106 x 249 cm.

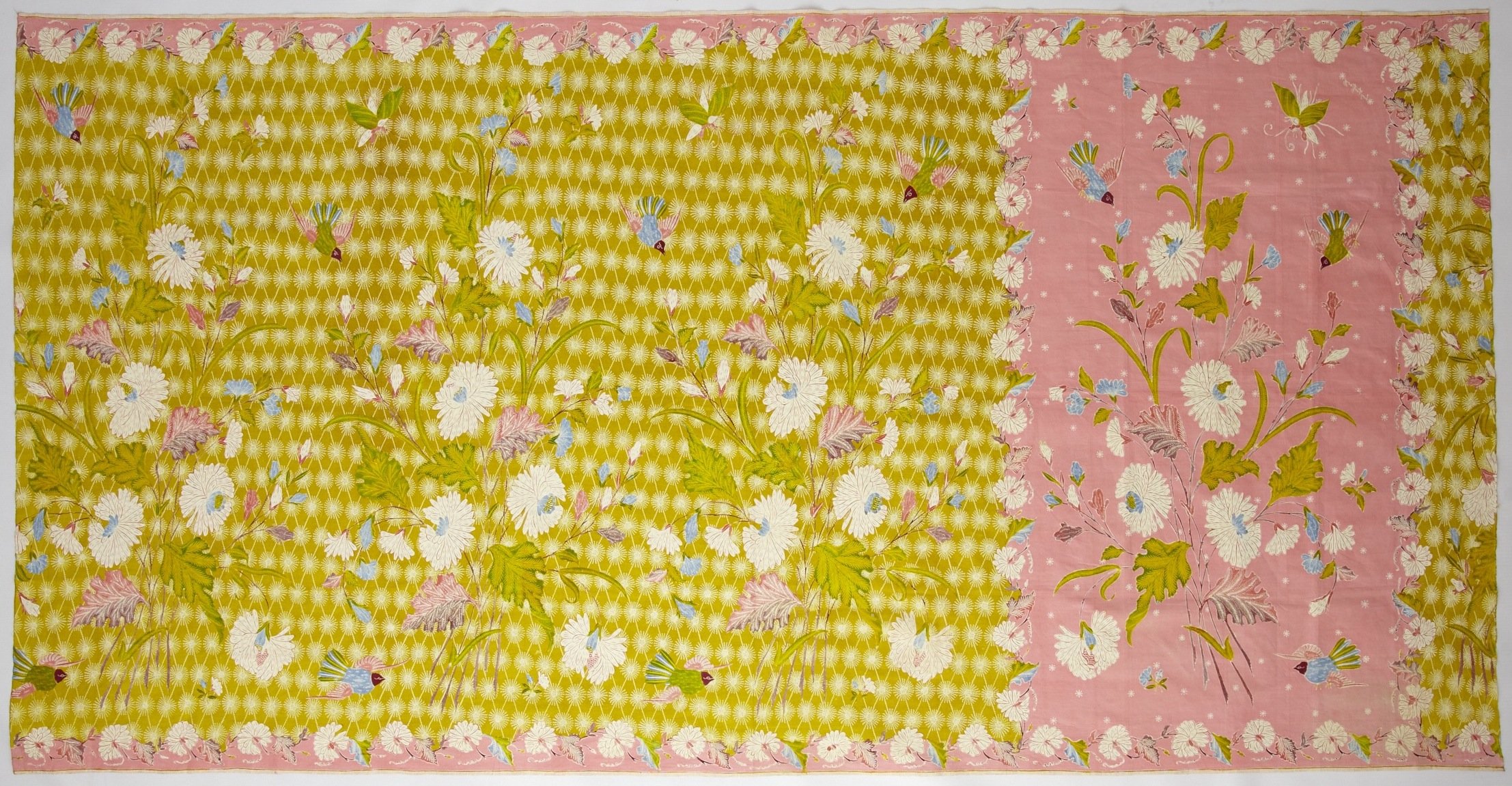

Pagi-Sore. Long Cloth, produced in Garut, about 1950. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 106 x 250 cm.

Rose Composition. Long Cloth, signed by Tjie King Sian, Purwokerto, about 1950. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 105 x 262 cm.

Peek a Boo (Cilukba). Long Cloth, produced in Pekalongan, about 1920. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 102 x 259 cm.

Male Javanese Birth Calendar. Long Cloth, produced by Kushardjanti, Yogyakarta, about 1978. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 101 x 264 cm.

Parang Godong Glinding (Wheel of Life). Long Cloth, produced by K.R.T. Hardjonagoro Go Tik Swan, Surakarta, about 2011. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 103 x 263 cm.

Raditya Kusumo on Cecek. Long Cloth, produced by K.R.T. Hardjonagoro Go Tik Swan, Surakarta, about 2011. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 106 x 257 cm.

Parang Klithik and Flower Bouquet. Long Cloth, produced in Banyumas, about 1920. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 105 x 244 cm.

Bat Composition (Prosperity). Long Cloth, produced in Banyumas, about 1940. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 106 x 276 cm.

Pepe Flower. Long Cloth, produced in Banyumas, about 1920. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 104 x 248 cm.

Truntum and Peacock. Long Cloth, produced in Surakarta, about 1950. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 104 x 253 cm.

Kopi Tutung. Tubular Cloth, produced by Tiga Negeri, Solo-Lasem-Kusus, about 1900. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 100 x 208 cm.

Tiga Negeri. Tubular Cloth, produced by Tiga Negeri, Solo-Lasem-Kudus, about 1950. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 105 x 180 cm.

Tiga Negeri. Tubular Cloth, produced by Tiga Negeri, Solo-Lasem-Kudus, about 1950. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 106 x 208 cm.

Hip Wrapper, produced by Eliza van Zuylen batik atelier, about 1910-20. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 106 x 207 cm.

Deer and Peacock. Hip Wrapper, produced in Pekalongan, about 1910-1920. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 107 x 247 cm.

Hip Wrapper, produced in Pekalongan, about 1910-1920. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 105 x 247 cm.

Hip Wrapper, produced in Lasem, about 1910-1920. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 103 x 256 cm.

Hip Wrapper, produced in Lasem, about 1910-1920. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 105 x 257 cm.

Flower Bouquet, Morning Evening. Hip Wrapper, produced in Pekalongan, about 1950-1960. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 106 x 253 cm.

Roses on Morning Evening. Hip Wrapper, produced in Pekalongan, about 1960-1970. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 108 x 257 cm.

Flower Bouquet over Rice Grains. Hip Wrapper, produced in Pekalongan, about 1960-1970. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 104 x 249 cm.

Hip Wrapper, produced in Pekalongan, about 1942-1945. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 104 x 207 cm.

Twelve Peacocks. Hip Wrapper, produced in Pekalongan, about 1960-1960. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 104 x 252 cm.

Prawns. Hip Wrapper, produced in Banyumas, about 1940. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 105 x 256 cm.

Patchwork. Hip Wrapper, produced in Pekalongan, about 1960-1970. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 104 x 245 cm.

Roses on Morning Evening. Hip Wrapper, produced in Pekalongan, about 1960-1970. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 104 x 241 cm.

Adek Bayi (Baby Carrying Cloth), produced in Pekalongan, about 1960-1970. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 104 x 255 cm.

Hip Wrapper, produced in Pekalongan, about 1960-1970. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 102 x 251 cm.

Fans on Terang Bulan. Hip Wrapper, produced in Garut, about 1970. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 103 x 250 cm.

Blue Terang Bulan. Hip Wrapper, produced in Garut, about 1970. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 103 x 245 cm.

Sky Blue Terang Bulan. Hip Wrapper, produced in Pekalongan, about 1970. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 106 x 235 cm.

Red-Orange Terang Bulan. Hip Wrapper, produced in Pekalongan, about 1970. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 103 x 242 cm.

Pink-Red Terang Bulan. Hip Wrapper, produced in Pekalongan, about 1970. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 104 x 245 cm.

Maroon-Red Terang Bulan. Hip Wrapper, produced in Pekalongan, about 1970. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 103 x 248 cm.

Brown Terang Bulan. Hip Wrapper, produced in Pekalongan, about 1970. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 104 x 245 cm.

Gentongan Panji Susi. Hip Wrapper, produced in Madura, about 2000. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand drawn genthogan dye, 105 x 199 cm.

Gentongan Tapote. Hip Wrapper, produced in Madura, about 2015. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand drawn gethongan dye, 103 x 242 cm.

Child's Hip Wrapper, produced in Pekalongan, about 1900-1910. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 87 x 154 cm.

Violin Hip Wrapper, produced in Pekalongan, about 1920. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 97 x 214 cm.

Geese Hip Wrapper, produced in Lasem or Pekalongan, about 1920. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 100 x 212 cm.

Hip Wrapper, produced in Pekalongan, about 1940. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 101 x 206 cm.

Lotus Garden Hip Wrapper, produced in Pekalongan, about 1930. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 98 x 209 cm.

Peacock and Flower Hip Wrapper, produced in Pekalongan, about 1920. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 96 x 222 cm.

Lengko-Lengko Hip Wrapper, produced in Pekalongan, about 1920. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 106 x 212 cm.

Geometric Tumpal Hip Wrapper, produced in Cirebon, about 1940. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 128 x 210 cm.

Rafiah Hip Wrapper, produced in Cirebon, about 1950. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 108 x 206 cm.

Kawatan Hip Wrapper, produced in Pekalongan, about 1940. Machine spun cotton, natural and synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 105 x 200 cm.

Maroon Lotus Garden Hip Wrapper, produced in Pekalongan, about 1930. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 109 x 212 cm.

Kilin Tokwie Altar Cloth, produced in Pekalongan, about 1950. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 98 x 101 cm.

Fruit Hip Wrapper, produced in Jakarta, about 1950. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 105 x 257 cm.

Hip Wrapper, produced in Jakarta, signed by Setiawati, about 1950. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 103 x 184 cm.

Tluki Hip Wrapper, produced in Cirebon, about 1950. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 106 x 256 cm.

Hip Wrapper, produced in Cirebon, about 1950. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 103 x 249 cm.

Hip Wrapper, produced in Cirebon, about 2010. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 103 x 258 cm.

Love Hip Wrapper, produced in Pekalongan, about 2010. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 104 x 267 cm.

Forest Hip Wrapper, produced in Pekalongan, about 2010. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 104 x 271 cm.

Garuda Bird Hip Wrapper, produced in Pekalongan, about 2010. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 101 x 169 cm.

Flowers Hip Wrapper, produced in Pekalongan, about 2012. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 104 x 270 cm.

Lotus Garden Hip Wrapper, produced by BINhouse, Jakarta, about 2016. Hand woven silk, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 108 x 241 cm.

The Wheel of Life Hip Wrapper, produced by BINhouse, Jakarta, about 2015. Hand woven silk, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 110 x 227 cm.

Starfish Hip Wrapper, produced by BINhouse, Jakarta, about 2010. Hand woven silk, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 107 x 236 cm.

Drizzling Rain Hip Wrapper, produced by BINhouse, Jakarta, about 2010. Hand woven silk, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 111 x 241 cm.

Slobok Shoulder Cloth, produced by BINhouse, Jakarta, about 2012. Cashmere, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 105 x 210 cm.

Breast Cloth, produced in Surakarta, about 1940. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 63 x 260 cm.

Breast Cloth, produced in Tiga Negeri, about 1950. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 51 x 256 cm.

Breast Cloth, produced in Banyumas, about 1950. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 53 x 263 cm.

Pasar Market Hip Wrapper, produced in Surakarta, about 2015. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 103 x 270 cm.

Dinosaur Hip Wrapper, produced in Surakarta, about 2012. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 103 x 267 cm.

Rabbit Hip Wrapper, produced in Surakarta, about 2012. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 102 x 207 cm.

Wirasat Hip Wrapper, produced in Surakarta, about 1960. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 102 x 252 cm.

Bokor Kencono Hip Wrapper, produced in Surakarta, about 1960. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 103 x 253 cm.

Nitik Hip Wrapper, produced in Surakarta. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 103 x 257 cm.

Mimi and Mintuno Hip Wrapper, produced in Surakarta, about 2000. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 100 x 251 cm.

Ceplok Madubrongto Hip Wrapper, produced in Surakarta, about 2000. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 109 x 242 cm.

Hip Wrapper, produced in Madura, about 2000. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 103 x 258 cm.

Sidoasih Hip Wrapper, produced in Surakarta, about 2000. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 105 x 252 cm.

Nagaraja Hip Wrapper, produced by Iwan TIrta batik atelier, Jakarta, about 2000. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 112 x 290 cm.

Eight Butterflies Hip Wrapper, produced in Surakarta, about 1950. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 103 x 252 cm.

Butterflies and Cards Hip Wrapper, produced in Surakarta, about 1950. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 103 x 247 cm.

Slobok Hip Wrapper, produced by Go Tok Swan Panembahan Hardjonegoro, Surkarta, about 1970. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 103 x 266 cm.

Segaran Sea Creatures Hip Wrapper, produced in Surakarta, about 2000. Machine spun cotton, natural and synthetic dyes, hand drawn wax resist dye, 103 x 270 cm.

Segaran Shrimp Hip Wrapper, produced in Surakarta, about 2000. Machine spun cotton, natural and synthetic dyes, hand drawn wax resist dye, 103 x 250 cm.

Segaran Eels, Prawns, and Fish Hip Wrapper, produced in Surakarta, about 2000. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 103 x 264 cm.

Kukilo Hip Wrapper, produced by Hardjonegaran batik atelier (Supiyah Anggriyani), Surakarta, about 2008. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 102 x 261 cm.

Ceplok Sriwedari Hip Wrapper, produced by Hardjonegaran batik atelier (Supiyah Anggriyani), Surakarta, about 2008. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 109 x 251 cm.

Flowers and Sushimoyo Hip Wrapper, produced in Pekalongan, about 1950. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 105 x 250 cm.

Hip Wrapper, produced in Demak-Kudus, about 1950. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 104 x 232 cm.

Hip Wrapper, produced in Pekalongan, about 1950. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 106 x 231 cm.

Morning Evening Hip Wrapper, produced in Pekalongan, about 1960. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 105 x 244 cm.

The Dancing Birds Sarong, produced in Pekalongan, about 1930-40. Machine spun cotton, natural and possibly synthetic dyes, hand-drawn wax resist dye, 106 x 195 cm.

The Dancers Hip Wrapper, possibly produced by Eliza van Zuylen batik atelier, Pekalongan, about 1940. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand-drawn wax resist dye, 103 x 196 cm.

Peacock and Wisteria Hip Wrapper, produced in Pekalongan, about 1940. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand-drawn wax resist dye, 107 x 196 cm.

Blue Flowers Hip Wrapper, produced in Pekalongan, about 1920-1930. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 105 x 235 com.

Hip Wrapper, signed by Tjoe Tjiat Kwee, produced in Pekalongan, about 1950. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 108 x 202 cm.

Hip Wrapper, signed by The Tie Siet, produced in Pekalongan, about 1940. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 106 x 203 cm.

Hip Wrapper, signed by Phoa Tjong Ling, produced in Pekalongan, about 1920-1930. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 106 x 207 cm.

Hip Wrapper, signed by Liem Giok Kwie, produced in Pekalongan, about 1930. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 102 x 214 cm.

Morning Evening Hip Wrapper, produced in Pekalongan, about 1942-1945. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 108 x 248 cm.

Morning Evening Hip Wrapper, produced in Pekalongan, about 1943. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 106 x 243 cm.

Morning Evening Hip Wrapper, produced in Pekalongan, about 1942-1945. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 106 x 250 cm.

Morning Evening Hip Wrapper, produced in Pekalongan, about 1942-1945. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 106 x 264 cm.

Morning Evening Hip Wrapper, signed by Oey Giok Kim, produced in Pekalongan, about 1945. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand drawn wax resist dye, 105 x 244 cm.

Morning Evening Hip Wrapper, produced in Pekalongan, about 1945-1950. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand-drawn wax-resist dye, 108 x 252 cm.

Hip Wrapper, produced in Pekalongan, about 1950. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand-drawn wax-resist dye, 105 x 241 cm.

Wing of Bird Hip Wrapper, produced in Pekalongan, about 1950. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand-drawn wax-resist dye, 105 x 257 cm.

Wajikan Hip Wrapper, produced in Pekalongan, about 1950. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand-drawn wax-resist dye, 104 x 259 cm.

Jlamprang Hip Wrapper, produced in Pekalongan, about 1950-1960. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand-drawn wax-resist dye, 102 x 251 cm.

Jlamprang Hip Wrapper, produced in Pekalongan, about 1950-1960. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand-drawn wax-resist dye, 104 x 258 cm.

Mother Earth Hip Wrapper, signed by Sapuan, produced in Pekalongan, 2010. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand-drawn wax-resist dye, 103 x 207

The Old Semarang Train Station Hip Wrapper, produced in Pekalongan, about 1900-1910. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand-drawn wax-resist dye, 100 x 210 cm.

Alphabet Hip Wrapper, produced in Pekalongan, about 1910-1920. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand-drawn wax-resist dye, 95 x 212 cm.

Hip Wrapper, produced by Eliza van Zuylen batik atelier, Pekalongan, about 1920-1930. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand-drawn wax-resist dye, 110 x 225 cm.

Plane, Boat, and Soldier Hip Wrapper, produced in Pekalongan, about 1920-1930. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand-drawn wax-resist dye, 102 x 179 cm.

Hip Wrapper, produced in Pekalongan, about 1950-1960. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, wood block printed wax-resist dye, 108 x 247 cm.

Hip Wrapper, produced by Dudung, Pekalongan, about 2016. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand-drawn wax-resist dye, 114 x 255 cm.

Sarong, signed by Mef. Hooberhat, produced in Pekalongan, about 1930. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand-drawn wax-resist dye, 110 x 225 cm.

Sarong, signed by Mien L Fredriks, produced in Pekalongan, about 1930. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand-drawn wax-resist dye, 106 x 189 cm.

Mother Earth Hip Wrapper, signed by Sapuan, produced in Pekalongan, 2010. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand-drawn wax-resist dye, 104 x 266 cm.

Naga Shirt Material, produced by Ozzy Batik, Pekalongan, about 2010. Hand woven silk, synthetic dye, hand-drawn wax-resist dye, 104 x 244 cm.

Hip Wrapper, produced by Hardjonegaran batik atelier, Surakarta, about 2011. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand-drawn wax-resist dye, 104 x 262 cm.

Clothing Fabric, produced by Nur Cahyo, Pekalongan, about 2016. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand-drawn wax-resist dye, 104 x 309 cm.

Organza Terracotta Gown, produced by Edward Hutabarat, Jakarta, about 2016.

Altar Cloth, produced in Lasem, about 1900. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand-drawn wax-resist dye, 102 x 107 cm.

Hip Wrapper, produced in Lasem for Sumatra. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, wood block printed wax-resist dye, 105 x 265 cm.

Tubular Cloth, produced in Lasem for Sumatra, about 1900. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand-drawn wax-resist dye, 107 x 202 cm.

Tubular Cloth, produced in Lasem, about 1900. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand-drawn wax-resist dye, 100 x 208 cm.

Tubular Cloth, produced in Cirebon, about 1940. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand-drawn wax-resist dye, 98 x 206 cm.

Tubular Skirt, produced in possibly Cirebon or Pekalongan, about 1930-1940. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand-drawn wax-resist dye, 104 x 204 cm.

Sea Creature Hip Wrapper, produced in Cirebon, about 1940. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand-drawn wax-resist dye, 102 x 245 cm.

Indian Dolls Hip Wrapper, produced by Katura batik atelier, Cirebon. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand-drawn wax-resist dye, 102 x 282 cm.

Camels Hip Wrapper, produced by Katura batik atelier, Cirebon, about 2012. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand-drawn wax-resist dye, 104 x 265 cm.

Banji and Rabbits Hip Wrapper, produced by Katura batik atelier, Cirebon, about 2012. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand-drawn wax-resist dye, 112 x 272 cm.

Lucky Spider Hip Wrapper, produced in Garut, about 1970. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand-drawn wax-resist dye, 104 x 244 cm.

Badminton Hip Wrapper, produced in Garut, about 1970. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand-drawn wax-resist dye, 104 x 246 cm.

Hip Wrapper, produced in Banyumas, about 1940. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand-drawn wax-resist dye, 106 x 247 cm.

Badminton Hip Wrapper, produced in Banyumas, about 1970. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand-drawn wax-resist dye, 105 x 246 cm.

Hip Wrapper, produced in Tan Sam Khin, about 1950. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand-drawn wax-resist dye, 106 x 254 cm.

Hip Wrapper, produced by Ciptoning Mintaraga, Yogyakarta, about 1950. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand-drawn wax-resist dye, 103 x 253 cm.

Hip Wrapper, produced in Yogyakarta, about 1950. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand-drawn wax-resist dye, 103 x 247 cm.

Young Prince Hip Wrapper, produced in Yogyakarta, about 1950. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand-drawn wax-resist dye, 103 x 252 cm.

Poleng Naga Hip Wrapper, produced in Yogyakarta, about 1960. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand-drawn wax-resist dye, 102 x 240 cm.

Snail Pattern Hip Wrapper, produced by Haryani Winotosastro batil atelier, Yogyakarta, about 2010. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand-drawn wax-resist dye, 105 x 234 cm.

Buket Pakis Hip Wrapper, produced by Puro Mangkunegaran batik atelier, Surkarta, about 1950. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand-drawn wax-resist dye, 103 x 249 cm.

Sri Rejeki Hip Wrapper, produced in Surakarta, about 1950. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand-drawn wax-resist dye, 103 x 254 cm.

Birds and Flowers Hip Wrapper, produced by Panembahan Hardjonegoro Go Tik Swan, Surkarta, about 1970. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand-drawn wax-resist dye, 101 x 264 cm.

Birds and Flowers Hip Wrapper, produced by Panembahan Hardjonegoro Go Tik Swan, Surkarta, about 1970. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand-drawn wax-resist dye, 102 x 262 cm.

Srihana Hip Wrapper, produced by Panembahan Hardjonegoro Go Tik Swan, Surkarta, about 1970. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand-drawn wax-resist dye, 103 x 245 cm.

Guardian of the Night Hip Wrapper, produced by Hardjonegaran batik atelier, Surakarta, about 2010. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand-drawn wax-resist dye, 103 x 261 cm.

Guardian of the Night Hip Wrapper, produced by Hardjonegaran batik atelier, Surakarta, about 2011. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand-drawn wax-resist dye, 103 x 250 cm.

Zebras Hip Wrapper, produced by Tatik Sri Harta batik atelier, Surakarta, about 2011. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand-drawn wax-resist dye, 102 x 265 cm.

The Monkey Family Hip Wrapper, produced by Tatik Sri Harta batik atelier, Surakarta, about 2011. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand-drawn wax-resist dye, 101 x 261 cm.

Tubular Skirt, produced in Madura, about 2008. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand-drawn wax-resist dye, 104 x 196 cm.

Forest Hip Wrapper, produced by Maimuna Pesona, Madura, about 2016. Machine spun cotton, natural dye, hand-drawn wax-resist dye, 104 x 247 cm.

Drizzling Rain Stole, produced by BINhouse, Jakarta, about 2014. Cashmere, synthetic dye, hand-drawn wax-resist dye, 73 x 210 cm.

Seaweed Stole, produced by BINhouse, Jakarta, about 2013. Cashmere, synthetic dye, hand-drawn wax-resist dye, 101 x 201 cm.

Rice Paddy Field Hip Wrapper, produced by BINhouse, Jakarta, about 2013. Hand-woven silk, synthetic dye, hand-drawn wax-resist dye, 113 x 230 cm.

Hip Wrapper, produced by BINhouse, Jakarta, about 2013. Machine spun cotton, synthetic dye, hand-drawn wax-resist dye, 101 x 168 cm.

“My love of batik tulis is equal to my love of good books.”

— Dr. Etty Indriati